Too Much Information: Exposition and the Reading Brain

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THIS POST!

“What you need to know in order to write a story is not what I need to know in order to read it.”

The other day an editing client asked, “How should I handle exposition?” Is it better, he wondered, to put it in dialogue? In the character’s thoughts? Or just have the narrator tell it?

There’s a tendency among many writers, myself included, to explain too much, and I’ve become ruthless about weeding out as much exposition as possible. So my gut reaction to the client’s question was, “None of the above. Get rid of it.”

But this client is writing a story with an epic fantasy setting. How can the reader enter the world he’s built—a world complete with non-human characters, its own social structures, and a long history—unless the narrator explains some of it? Simply deleting every explanation isn’t a sound editorial strategy.

In this article we’ll consider what exposition is. We’ll see why we can’t get rid of it altogether, and we’ll learn how brain science can help us understand when to use it and why. At the end, we’ll be a big step closer to writing novels that glide along on story-rails with the least possible friction.

WHAT EXACTLY IS EXPOSITION?

“Exposition is a literary device used to introduce background information about events, settings, characters, or other elements of a work to the audience or readers. The word comes from the Latin language, and its literal meaning is ‘a showing forth.’ Exposition is crucial to any story, for without it nothing makes sense.” —Literary Devices.net

“Exposition means facts—the information about setting, biography, and characterization that the audience needs to know to follow and comprehend the events of the story.” —Robert McKee, Story (p. 334).

McKee goes on to extol the famous writers’ axiom “Show, don’t tell,” and he devotes an entire chapter to the craft of disguising exposition.

So which is it? Is exposition necessary? Or is it so undesirable that it needs to be disguised?

It’s both. Trouble is, the “Show Don’t Tell” evangelists never explain why we have to hide our exposition. They just vaguely imply that exposition is somehow against the rules because it’s “boring.”

As explanations go, that’s pretty weak. After all, you’ve found a way to put your visions and inventions on the page, often in carefully-crafted prose. It’s not boring to you. You’re going to need a more convincing reason than “it’s boring” before you’re ready to remove it.

EXPOSITION AND BRAINWORK

To understand why exposition is a such a challenge in fiction, let’s have a little brain science.

Steven Pinker, in The Sense of Style, tells us that human working memory can hold only four or five items at a time. This is a severe mental limitation, but we work around it with a process called “chunking.”

Chunking is when we group ideas so that together they occupy only one of the four or five available memory slots in our brain. Pinker gives this example:

M D P H D R S V P C E O I H O P

It looks random and meaningless, doesn’t it? It would take a fair amount of brain energy to force even a few of those 16 letters into your memory.

But if you group the letters as MD PHD RSVP CEO and IHOP, you now have five chunks, each containing meaning—effectively five recognizable “words.” The amount of brain energy it took you to absorb that string dropped dramatically.

And if you can package those five chunks into a coherent story, you create a single larger chunk that occupies only one memory slot, leaving the other three or four open for other stories.

“The MD and the PhD RSVP’d to the CEO of IHOP.”

Read that once—ideally aloud—and chances are that you can remember it and repeat it. (Of course there’s some cultural context here. IHOP, for those outside North America, is the International House of Pancakes, a restaurant chain.)

What does this tidbit of brain science have to do with exposition? Simply this: exposition in a story is analogous to M D P H D R S V P C E O I H O P. It’s new, un-chunked information, and taking it in requires masses of brain processing power.

Exposition, in other words, makes the reader work.

Novelists, especially new novelists, often feel that their exposition is helping the reader do less work because it clarifies the story…explains things…teaches the reader what they need to know in order to keep up with the plot.

The trouble with that belief—and some writers are remarkably insistent on it—is that we don’t open a novel in the hope of exercising our brains. We pick up a novel to be entertained, to enjoy core emotions like excitement, thrills, or risk. We read a story in order to be carried away to strange lands and thrilling adventures, to sigh over true love, weep at misfortune, and forget the trials of our own daily lives.

We read novels to feel, not to think. We read them to relax, not to work. Our personal definitions of reading pleasure may range from the simplest love story to the most complex literary novel, but we still read novels for enjoyment.

We might absorb “The MD and the PhD RSVP’d to the CEO of IHOP,” but it’s still work. We still have to do some translating in our heads.

But present it as “A couple of smart women ate pancakes with a high-powered executive,” and it slides into our consciousness with almost no effort at all. Do we care which woman has which degree? Maybe. Do we need to know? Possibly. Do we need to know it while they’re having breakfast with the head of the restaurant chain? Probably not.

The less brainwork a novel makes us do, the longer we’ll stay up turning pages, enjoying those pancakes along with the highly educated protagonist and her sidekick.

Maybe you’re not writing fluffy pancakes. Maybe you’re more of an eggs-benedict-with-hollandaise writer. Your target reader has chosen your book because it has intellectual cachet, and they’re willing to put more brainpower into reading it. That’s okay. The principles of reading ease can scale. Why make even a very literary novel harder to read than it needs to be?

TWO COMMON EXPOSITION FAULTS

The two exposition problems I see most often in my clients’ work are:

Over-reliance on the Big Block of Explanation.

Acrobatic contortions to avoid the Big Block of Explanation, in adherence to the mighty Show Don’t Tell rule.

Let’s look at each one of them in turn.

THE BIG BLOCK OF EXPLANATION

Here’s a purely made-up example of the Big Block of Explanation:

“Let’s go to the mall,” Heather said.

Imani thought back to the last time she had been to the mall. The terror she had felt at the sound of the first shot fired, the screams of people fleeing for their lives, the crash of displays falling over as customers dove under racks and counters for cover. It had been the worst day of her life.

“I don’t want to go,” Imani replied.

However vivid Imani’s recollection is in that middle paragraph, it does little to reveal her character. It explains some things about Imani, but it’s an info-dump—a Big Block of Explanation.

The block interrupts the action—that is, the dialogue between Heather and Imani—by referring you to a past whose details may or may not be relevant at this point in the story. Here’s what happens in your brain:

You expend energy time-jumping to Imani’s past.

You process terror, shots fired, screams, crashes, and people diving under racks. By the time you get to Imani’s response, all your memory slots are engaged, and you’ve lost sight of what Heather said.

So you expend more brainpower backtracking in the text to remind yourself of Heather’s initial suggestion.

Now, you might be willing to make that effort—to glance up the page and re-read—but if you happen to be an audiobook listener rather than a reader, you’re certainly not going to take the trouble. Either way, the extra brain-fuel you’ve just expended is debited from your attention account, and as that account balance drops, the story will start to feel like work.

I don’t know about you, but when a story starts to feel like work, I put it down.

CONTORTIONS TO AVOID THE BIG BLOCK OF EXPLANATION

How about the second type of fault, where the writer bends over backward to avoid the Big Block of Explanation? Here’s what I mean:

“Let’s go to the mall,” Heather said.

Imani glared at her. “You know I can’t face going to the mall, Heather.”

“I’m sorry,” Heather said. “I’d forgotten about the time you were there when that gunman shot the place up.”

“That’s right. So I don’t want to go.”

This is what I call the “As You Know, Bob” error. The characters are telling each other things they both already know, in order to inform the reader of something. It’s not only cringingly unnatural, but it commandeers almost as much reader brainpower as the first example. Even if you’re willing to forgive the unnaturalness of the dialogue, you’re forced to pause and process that past event before moving ahead with the present story.

THE BRAINWORK FRAMEWORK

Exposition can take a variety of forms, and some of them require more reader brainwork than others. Here are six common ones, from the most brain-intensive to the least:

Purely explanatory information from the narrator directly to the reader. This is naked exposition. No disguise at all. It serves one purpose: to explain something to the reader. It’s the form that most often evokes a “Show Don’t Tell!” scold from critique partners and beta-readers. This doesn’t mean that you should never use it. It just means that you shouldn’t use it where the reader’s brainpower is already low. More on this later.

A character’s inner thoughts. Also known as the free indirect style, this is a thin disguise for exposition, best used only when it performs the dual tasks of revealing character while explaining something. We engage emotionally with characters much more easily than we can process an explanation.

Flashbacks. A lot like character’s inner thoughts, but usually set apart in the text by a scene break. This allows the reader to process the flashback as the fresh beginning of a new story—that is, by freeing up memory slots. Note, though, that it’s hard work keeping track of the complex timelines flashbacks create.

Descriptive passages. These take take less brainwork to process than abstract explanations, because most readers already have a ready sensory vocabulary of colors, shapes, sounds, smells, etc. Similarly, they can call up images of clouds, mountains, trees, buildings, streets, and so forth, without working very hard.

Dialogue. Dialogue is technically action (the characters are doing something—speaking), so by definition it’s more immediately immersive and less “explainy” than straight exposition. But beware of the “As You Know, Bob” fault if you use dialogue to disguise exposition.

Letters, diaries, news reports, transcripts, and the like. This is the epistolary narrative device, and it can work in almost any kind of story. Like forms of dialogue, epistolary elements give a sense of immediacy. Reading the newspaper along with a character is much more engaging than being told about the article. The trick is not to cram in a lone epistolary element to solve an exposition problem. It should be one of several, a narrative device that runs throughout your story.

EXPOSITION AND NARRATIVE DRIVE

Exposition is sometimes necessary, but it’s amazing how often it’s not. Here’s our little Imani and Heather scene without it:

“Let’s go to the mall,” Heather said.

Imani glared at her. “Are you kidding me?”

“Okay, okay. Never mind.”

This version leverages that magical thing called narrative drive. Narrative drive is what keeps a reader reading. The specific form of narrative drive here is mystery. That’s when the character knows more than the reader.

In this version, Imani knows why she doesn’t want to go to the mall, but you don’t. All you know is that for some reason, she’s opposed to it. From her glare and her choice of words, she seems afraid or angry. Something bad lies behind that. What could the problem be?

Heather might know about it, but either she’s forgotten or doesn’t care. Is she so self-centered? Or was it really not that big a deal?

Yes, these are questions. It’s questions, not answers, that create narrative drive. You keep reading until you find answers, and ideally you don’t get the last answer till the very end of the story.

(NB: Everything you need to know about narrative drive, Valerie Francis has brilliantly set forth in her articles on the subject. Links are at the end of this post.)

The Pandora effect

Why do questions create the narrative drive that keeps us reading?

In Greek mythology, Pandora is consumed by curiosity when someone gives her a closed box and tells her never to open it. She opens it. Bad things fly out.

If you had the box, would you open it? “The Pandora Effect” is the name researchers have given to the experimental finding that yes, you probably would. Why? Because human beings are curious.

Curiosity is one of the most fundamental traits of human existence. It’s the desire to close a gap in our knowledge. It drives us to explore, to invent, to solve problems in new ways. Without it, we’d still be living in caves. To bypass our powerful instinct for safety and survival, the curiosity instinct—which courts danger—must be at least as powerful.

And it is. The Pandora Effect is our counterintuitive tendency to risk danger in order to find out what’s in the box.

Raising questions in your story and leaving them unanswered for a while is like handing your reader that box. They will be eager to open it.

WHERE DOES EXPOSITION BELONG?

Well-written exposition can be engaging in its own right. Plenty of great classic novels are heavy on exposition—particularly those from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. Long passages of exposition can be interesting, charming, and stylish, and people still read those novels today.

But there’s a limit. No novel was ever more sprawlingly explainy than Moby Dick. Herman Melville knew everything about whaling, and by George he wants the reader to learn it too. That’s why modern readers can’t get through Moby Dick.

We are twenty-first century century readers. The most dedicated and enthusiastic of us have consumed a lifetime of stories via movies and television alongside our reading, and we don’t want a lot of explanations.

This isn’t just because attention spans have shrunk to the vanishing point (though that’s certainly a consideration). And it’s not solely because exposition requires brainwork.

It’s also because we’ve become far more sophisticated at consuming stories than our eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ancestors were. We’ve been trained to process stories faster, to take in small cues quickly. Unlike our great-grandparents, we don’t need the camera to linger on a clue for us to spot it, and we don’t need a narrator to explain our characters’ every action or utterance in detail. We get it, already.

Are you beginning to feel that this supposedly “necessary” thing called exposition doesn’t belong anywhere?

Almost but not quite true. Blocks of explanatory material have very little place in a modern novel, but they aren’t completely disallowed. The most likely place in any story for some straight up exposition is at the beginning.

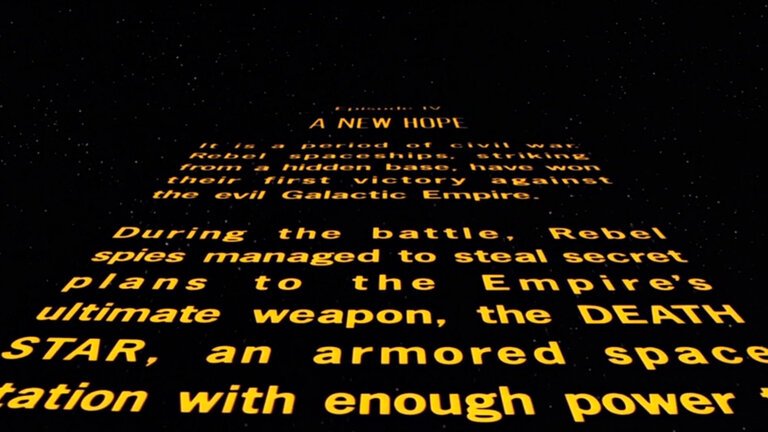

“Once upon a time, there were three bears…” or “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” or “It began with the forging of the great rings…”

The reader’s brain is fresh at the beginning. Its memory slots are free. At that point, it can handle a little learning, a little instruction, a little scene-setting or world-building.

A little. Not pages and pages.

“At the beginning” isn’t limited to just the global opening. It can mean the start of an act or sequence; it can be when the story moves to a new setting, or introduces a new character. It can even be at the start of a new chapter. (Just don’t start every chapter with a block of explanation. I address the various ways to launch a scene in my article How To Launch a Scene.)

The worst place for exposition of any sort is in the middle of the action—including in the middle of dialogue. Putting a block of explanation there is like popping up in front of the movie screen to tell the audience what you know. Consciously or unconsciously, the reader wants you to sit down, shut up, let them enjoy the show.

SO YOU STILL HAVE SOME BLOCKS OF EXPOSITION…

…and you’re convinced that you can’t get rid of them. What do you do?

First, confirm that the information in each block of exposition genuinely serves the story. Does it turn a scene? Expose a character’s wants and needs? Reflect your story’s controlling idea? It is crucial to one of the obligatory scenes or conventions of your genre? Can the story work without it?

No matter how interesting and creative it is, no matter how much trouble you took to research and write it, if the story can work without it, it’s a candidate for the chopping block.

If it does serve the story, note the key story information it contains. In our Imani and Heather example above, that would be “Imani was present during a shooting” and maybe “Imani is traumatized.”

Then think through your story. What would happen if you put that information prior to her conversation with Heather? If the reader knows in advance that Imani was traumatized at the mall, then the mystery raised by that conversation will be lost.

But you gain a different form of narrative drive: dramatic irony. We know something that Heather doesn’t know. We shake our heads and think, “Oh, Heather, what a careless suggestion! You’re going to feel so bad when you find out.”

What would happen if you inserted the information later? Then the mystery raised by the conversation with Heather remains. Where best to solve that mystery (by revealing the information about Imani’s trauma) will depend on how pivotal a character Imani is, and how her trauma affects the story.

But if Imani’s trauma at the mall has no bearing on the story, remember: she’s a character, not a real person. You can remove that trauma as easily as you inflicted it.

SOME FINAL BRAINWORK NUMBERS

Say you’ve spent two and a half hours a day, five days a week for two years writing, editing, and polishing your novel of 100,000 words.

That’s 1300 hours of work.

The average reader can absorb fiction at about 250 words per minute—faster, if you’ve given them a real page-turner—so they will spend six or seven hours reading your novel.

This means that you spend 200 times more effort creating your novel than the reader will spend reading it.

And that’s exactly as it should be. If the ratio were any lower, it would mean that you’ve slowed the reader down with hard-to-process sentences. Obstacles. Friction.

And I hope it’s clear by now that a major source of friction in fiction is exposition.

Our love of our own creation tempts us all to leave details on the page that don’t drive the story forward. Some readers might forgive it, but if they leave reviews, they’ll include phrases like “takes a little getting into” or “rewards your patience.”

Many will give up, and if those readers leave reviews at all, they will say damning things like “did not finish,” “tedious,” or “hard to follow,” even though they won’t be able to say exactly why.

Here’s a tip: Nobody—not even the tolerant reader who loves nineteenth century novels—will ever complain because your story was a smooth joyride to read.

As the author, you’re the world-builder, the omnipotent deity of the universe of your novel. You need to have done all the research, character development, mapping, and timelines. You have to know all about the geography of your world, the backstories of its people, the socioeconomic system in which they live. You have to know the wants and needs, the trials and the triumphs, that have brought your characters into this story.

You have to do all the brainwork so that the reader has to do hardly any.

Then you need to tell a story.